Barbara Ernst Prey. Lineage and New Frontiers

MAINE WOMEN MAGAZINE

By Rachel Romanski, August, 2021

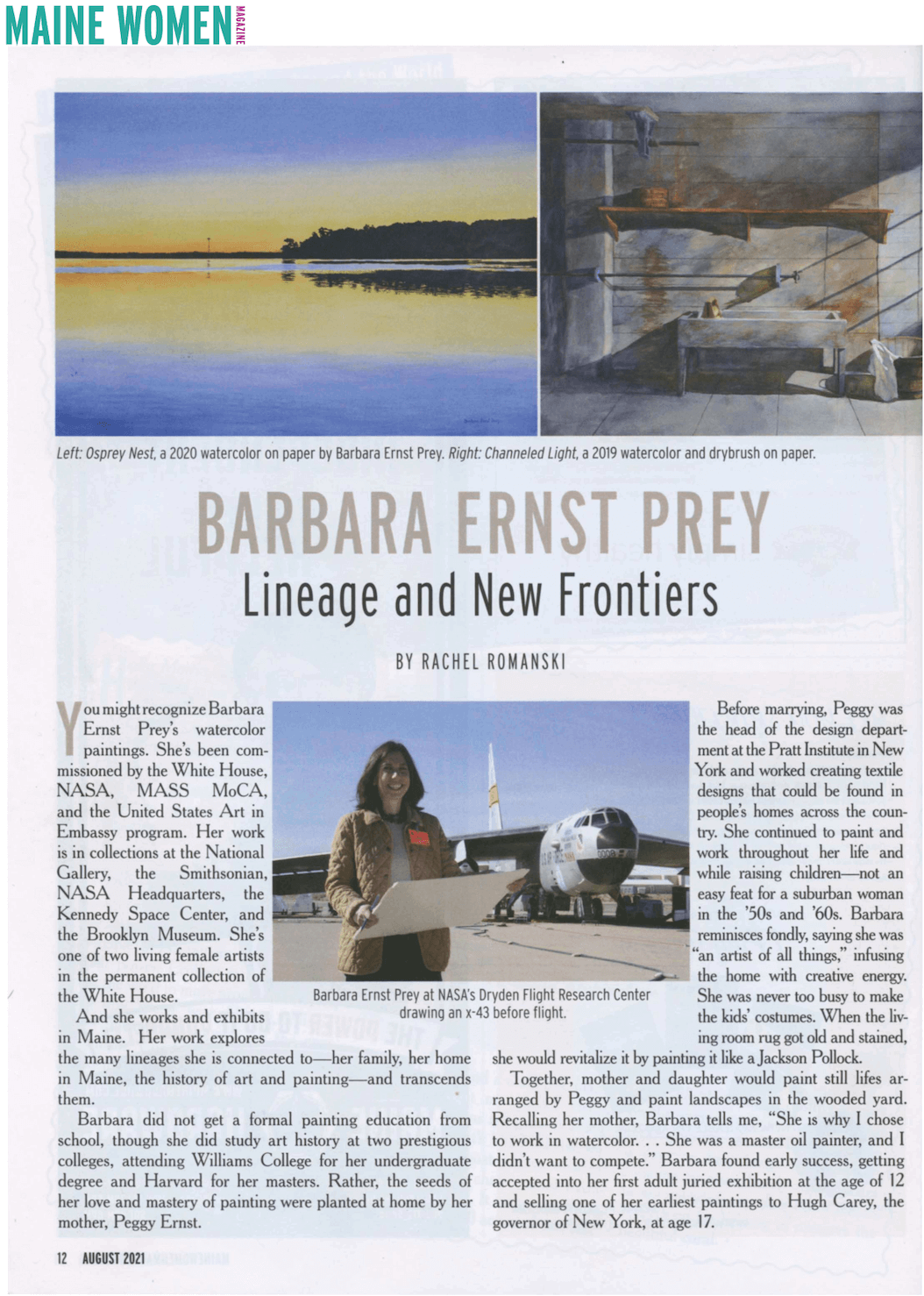

You might recognize Barbara Ernst Prey’s watercolor paintings. She’s been commissioned by the White House, NASA, MASS MoCA, and the United States Are in Embassy program. Her work is in collections at the National Gallery, the Smithsonian, NASA Headquarters, the Kennedy Space Center, and the Brooklyn Museum. She’s one of two living female artists in the permanent collection of the White House.

And she works and exhibits in Maine. Her work explores the many lineages she is connected to - her family, her home in Maine, the history of art and painting - and transcends them.

Barbara did not get a formal painting education from school, though she did study art history at two prestigious colleges, attending Williams College for her undergraduate degree and Harvard for her masters. Rather, the seeds of her love and mastery of painting were planted at home by her mother, Peggy Ernst.

Before marrying, Peggy was the head of the design department at the Pratt Institute in New York and worked creating textile designs that could be found in people’s homes across the country. She continued to paint and work throughout her life and while raising children – not an easy feat for a suburban woman in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Barbara reminisces fondly, saying she was “an artist of all things,” infusing the home with creative energy. She was never too busy to make the kids’ costumes. When the living room rug got old and stained, she would revitalize it by painting it like a Jackson Pollock.

Together, mother and daughter would paint still lives arranged by Peggy and paint landscapes in the wooded yard. Recalling her mother, Barbara tells me, “She is why I chose to work in watercolor… She was a master oil painter, and I didn’t want to compete.” Barbara found early success, getting accepted into her first adult juried exhibition at the age of 12 and selling on of her earliest paintings to Hug Carey, the governor of New York, at age 17.

Additionally, Peggy nurtured a love of Art History in her daughter, going on frequent trips to the grand museums of New York and pointing out flaws in the paintings of great masters. In college, Barbara went on to specialize in German Baroque Architecture and later received a Fulbright scholarship which brought her to Southern Germany for two years.

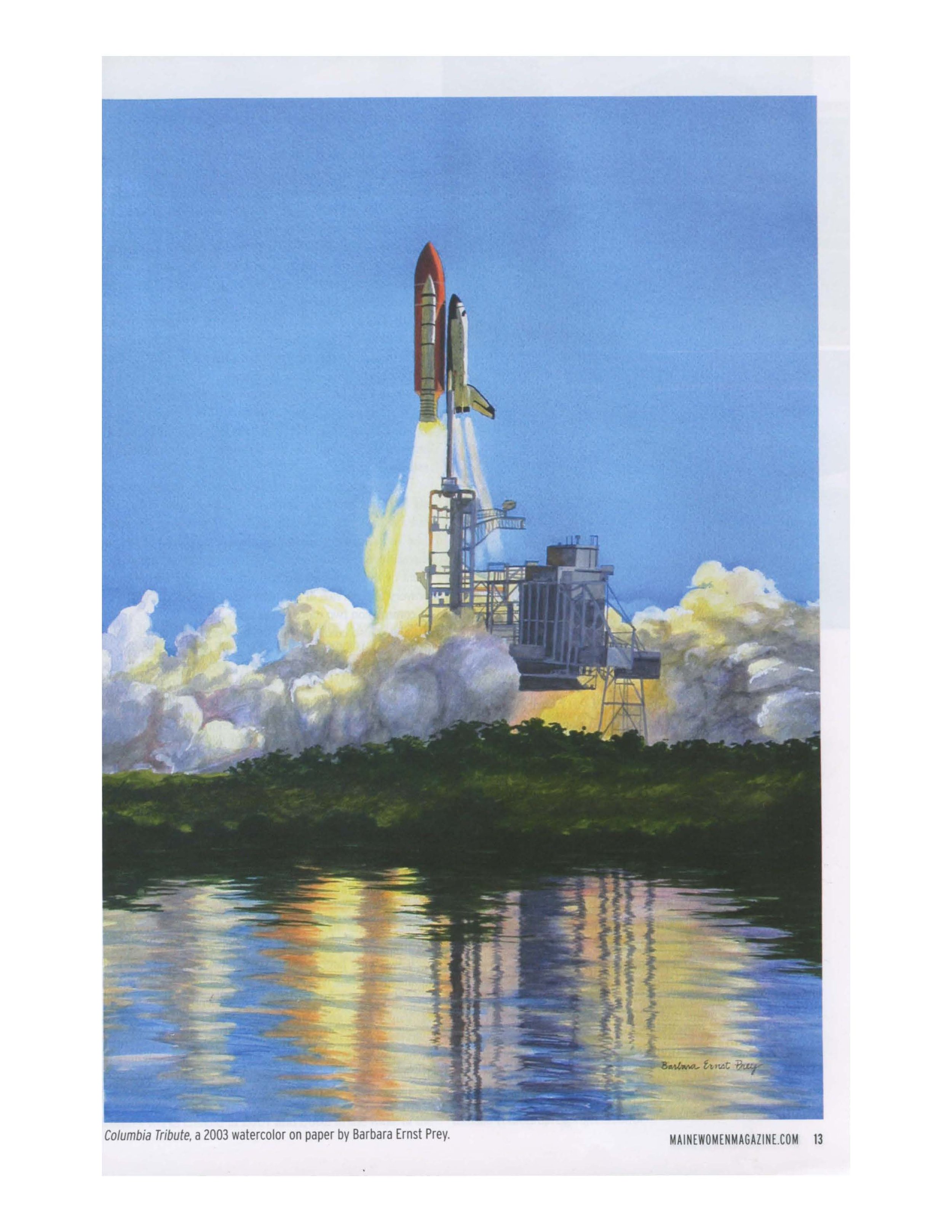

Columbia Tribute

You may notice, though, that her paintings have a distinct American Style. While at Williams College, situated in the scenic Western Massachusetts’ Berkshire Mounts, Barbara had access to two prestigious local museums: the Williams College Museum of Art and the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. Both have extensive collections of American art, including the paintings of Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, and many members of the Hudson River School. These painters highlighted natural beauty, pastoral landscapes, and quiet interior spaces.

There is a clear link between these artists of the past and Barbara Ernst Prey. She is a part of this lineage of (mostly male) painters who have found themselves drawn to Main for its beauty and its people. In her subject matter, we can see sunrises, clothes drying on a line, American flags on big white houses, marshlands, fishermen’s workshops, buoys, and so on. These scenes all have a timeless quality. During our Zoom conversation, she said that her paintings are not just about their subject matter but are more often about the capturing light and color relationship. It is these two elements that allow her to capture more than just a scene, but an entire feeling.

A self-described colorist, her unique method of watercolor painting involves many washes of paint which create a densely saturated palate. She also uses a research-oriented approach, studying her subjects intensely and focusing on not just looking, but seeing. Depending on the project, this approach can involve making many exploratory drawings, building models, talking to experts, and doing historical research. It is perhaps these unique and dedicated aspects of her practice that have helped to bring her incredible opportunities and success.

In 2002, NASA commissioned Barbara to paint the International Space Station before its completion. For this commission, she spoke with engineers, scientists, and astronauts, and she built scale models to work from. As one of the few female artists to ever be commissioned by the organization, she proved her mastery and was asked back in 2003 to paint a tribute to the Space Shuttle Columbia. Near the end of its 28th flight, upon re-entry to the atmosphere, this shuttle broke apart, killing the seven astronauts inside.

The stunning painting shows Columbia just seconds after take-off, with a beautiful Florida blue sky, and the colors of the propulsion reflecting brilliantly in the water around the space center. The moment she chose to portray is indicative of her incredible discernment. It is a moment of hope for all of humanity, the moment of ascension toward the unknown, and a celebration of the bravery and service of the individuals on board. NASA went on to commission two more works from her.

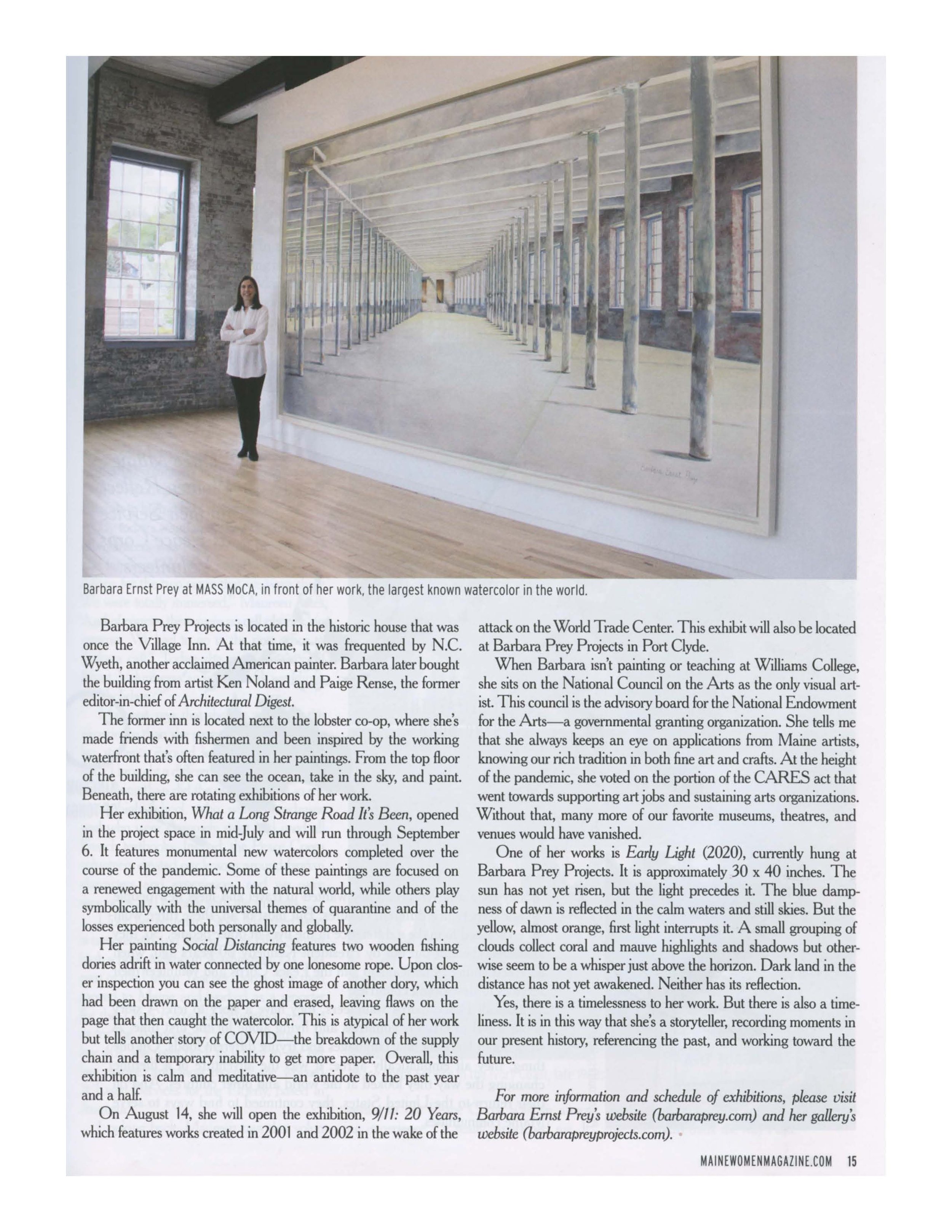

She is also credited with the largest known watercolor painting in the world. Measuring in at 8 x 15 feet, the painting was commissioned in 2016 by MASS MoCA, a contemporary art museum that is located in an old textile mill complex in the Northern Berkshires of Massachusetts. The painting depicts the interior of Building 6 of the mill, in its raw, unrenovated state. The addition of this building to the already spacious and numerous galleries made MASS MoCA the largest contemporary art museum in the country. So, of course: the largest watercolor for the largest museum.

Watercolor on paper, being one of the most unforgiving medias, made this feat truly remarkable. Liker her NASA works, and her 9/11 series, many of which were painted in Maine, it is a memorial to a particular time and place – a place with deep roots and history.

Barbara Ernst Prey at MASS MoCA, in front of her work, the largest known watercolor in the world.

Barbara splits her time between her homes and studios on the St. George Peninsula in Maine, in Western Massachusetts, and on Long Island, New York. She’s been summering (and painting) in Maine for over 40 years, but this tradition didn’t start with family vacations. Instead, she was brought here by a friend.

It was only later Barbara serendipitously discovered her deep familial ties to the Midcoast region. She tells me that her ancestors were among the first European-American settlers on the islands of Vinalhaven and North Haven – the Calderwoods and the Carvers, whose names are memorialized in the local Calderwood Neck and Carver Harbor. Her great-great-grandmother is buried on Owls Head. This is all amazingly synchronistic considering that she’s now owned and operated her own gallery in Port Clyde since 2000.

Barbara Prey Projects is located in the historic house that was once the Village Inn. At that time, it was frequented by N.C. Wyeth, another acclaimed American painter. Barbara later brought the building from artist Ken Noland and Paige Rense, the former editor-in-chief of Architectural Digest.

The former inn is located next to the lobster co-op, where she’s made friends with fishermen and been inspired by the working waterfront that’s often featured in her paintings. From the top floor of the building, she can see the ocean, take in the sky, and paint. Beneath, there are rotating exhibitions of her work.

Her exhibition, What a Long Strange Road It’s Been, opened in the project space in mid-July and will run through September 56. It features monumental new watercolors completed over the course of the pandemic. Some of these paintings are focused on a renewed engagement with the natural world, while others play symbolically with the universal themes of quarantine and of the losses experienced both personally and globally.

Her painting Social Distancing features two wooden fishing dories adrift in water connected by one lonesome rope. Upon closer inspection you can see the ghost image of another dory, which had been drawn on the paper and erased, leaving flaws on the page that then caught the watercolor. This is atypical of her work but tells another story of COVID – the breakdown of the supply chain and a temporary inability to get more paper. Overall, this is exhibition is calm and meditative – an antidote to the past year and a half.

On August 14, she will open the exhibition, 9/11: 20 Years, which features works created in 2001 and 2002 in the wake of the attack on the World Trade Center. This exhibit will also be located at Barbara Prey Project in Port Clyde.

When Barbara isn’t painting or teaching at Williams College, she sits on the National Council on the Arts as the only visual artist. This council is the advisory board for the National Endowment for the Arts - a governmental granting organization. She tells me that she always keeps an eye on applications from Maine artists, knowing our rich tradition in both fine art and crafts. At the height of the pandemic, she voted on the portion of the CARES act that went towards supporting art jobs and sustaining arts organizations. Without that, many more of our favorite museums, theatres, and venues would have vanished.

One of her works is Early Light (2020), currently hung at Barbara Prey Projects. It is approximately 30 x 40 inches. The sun has not yet risen, but the light precedes it the blue dampness of dawn is reflected in the calm waters and still skies. But the yellow, almost orange, first light interrupts it. A small grouping of clouds collect coral and mauve highlights and shadows but otherwise seem to be a whisper just above the horizon Dark land in the distance has not yet awakened. Neither has its reflection.

Yes, there is a timelessness to her work. But there is also a timeliness. It is in this way that she’s a storyteller, recording moments in our present history, referencing the past, and working toward the future.